Watch our talk by Prof. June Purvis, which will be available until the New Year

Catch up with our public lecture

Please enjoy the chance to watch the fascinating lecture from Dr Sumita Mukherjee, Bristol University, titled ‘Suffrage, Childhood and Home Life for Indian Girls in Early 20th Century England’. It will be available until the New Year.

Public Lectures co-hosted with the Pankhurst Centre

Public Lectures, hosted with the Pankhurst Centre

The Pankhursts and Politics: Part Two

Written by Saima Akhtar (Twitter: @saimathewriter)

Supervised by Dr Charlotte Wildman (Twitter: @TheHistoryGirrl)

As part of our Challenging Domesticity in Britain, 1890-1990 research network, we are dedicating a blog post to the extraordinary suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst.

Read Part One of our blog post here:

The Pankhurst Family and Politics: Part One

Part Two

When the First World War broke out, Emmeline and Christabel were patriotic, and publicly declared the end of militancy to support the British war effort. A clever strategy for the WSPU campaign, this allowed the suffragettes to declare a statement of loyalty to their country, as their campaign had been subject to public scrutiny. As the nation prepared for war, the suffragettes who had been imprisoned for activism were released by the government. It was also important to Emmeline that women entered the workforce whilst the men fought on the frontline. But Emmeline remained firm in her conviction that “when the clash of arms ceases… the demand (for women’s suffrage) will again be made.”[1]

The war became another point of contention for Sylvia. Very much a pacifist, Sylvia opposed the conflict, which further ostracised her from Emmeline. Extremely committed to socialism, Sylvia admired Lenin and was a co-founder of the British Communist Party (though she was later expelled). As Emmeline became disillusioned with socialism, Sylvia’s socialist views intensified. In 1926, she was utterly dismayed when she discovered that Emmeline intended to stand as a Conservative Party candidate in the next election.[2] This was a decision which Sylvia viewed as a betrayal of her father’s radical socialist principles. The rift between Sylvia and Emmeline was deepened, showing how politics divided the Pankhurst women.

When Sylvia served a stint in prison at Holloway in October 1906, she was horrified by the unsanitary conditions she experienced as an inmate. During this time, prisons were overcrowded, meals were meagre and prisoners were forced to carry out menial labour tasks. This gave Sylvia impetus to campaign for prison reform, which directly contradicted Christabel’s rule of keeping wider struggles separate from suffragette activism.[3] Again, this is another indicator that Sylvia and Christabel could not be civil, as the sisters disagreed on whether or not women’s suffrage ought to be their sole focus. Lastly, in 1927, much to Emmeline’s shock, Sylvia had a child out of wedlock, and the pair never reconciled.[4] Completely scandalised by Sylvia’s actions, Emmeline made no attempt to repair her relationship with her second daughter. This demonstrates that Emmeline had moral expectations for her children, perhaps more so because her activism had placed her in the public eye.

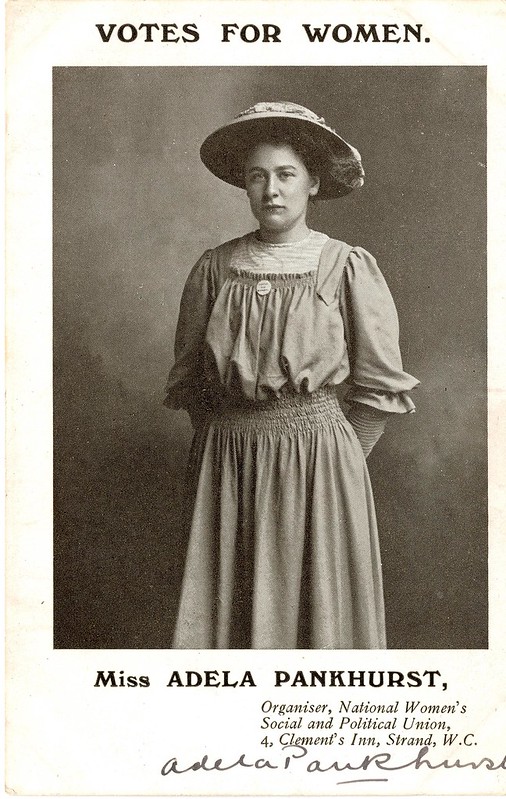

Emmeline’s devotion to women’s suffrage also caused tension for her third child, Adela. Like her sisters, Adela was a hard-working WSPU organiser, as she was tasked with breaking up Liberal Party meetings. However, Adela felt that Emmeline prioritised activism instead of being a present mother to her youngest child, Harry. Often a cause for his family’s concern, Harry suffered from various health issues and fell behind in his education. So, Emmeline enrolled him in different schools and trades including farming, construction and office work, meaning that there was instability in his life. In a 1933 account of her mother, Adela wrote that “it would have been treason to the Cause” if Emmeline gave up her public work to devote herself to Harry.[5] This use of political language (“treason”) conveys Adela’s resentment towards her mother, due to Emmeline’s work commitments. When Harry became critically ill in 1909, Emmeline undertook a lecture tour in America to pay for his medical care. The other Pankhursts chose not to disclose Harry’s illness to Adela, who, once again, viewed this as a “sacrifice to the Cause”.[6] Adela clearly felt abandoned, as she preferred Emmeline to focus on women’s suffrage.

Adela also became estranged from her mother and sisters. She felt that the WSPU strategies were too violent, so, like Sylvia, Adela was forced to leave the organisation in 1914. Concerned about her youngest daughter’s socialist and anti-militant views, Emmeline sent Adela on a one-way ticket to Australia, where she remained until her death in 1961.[7] Unsurprisingly, Emmeline was committed to militancy in her activism; she was not willing to entertain any activists who did not advocate militancy. In a letter dated 10th January 1913, Emmeline encouraged her fellow WSPU members to embrace militancy, writing: “If any woman refrains from militant protest against the injury done by the Government and the House of Commons to women and to the race, she will share the responsibility for the crime.”[8] It is clear from Emmeline’s tone that the WSPU members who did not meet her requirements would be dismissed. So, Adela’s punishment for the “crime” of not being militant was expulsion to Australia. The fact that Emmeline broke ties with her daughter illustrates that the Pankhurst household was heavily structured around the cause of women’s suffrage.

Emmeline later showed signs of wanting to reconcile with Adela. Before her death in 1928, Emmeline wrote to Adela, expressing regret for the estrangement between them.[9] A shared interest in conservative values may have sparked Emmeline’s attempt to communicate with Adela. In 1920, Adela co-founded the Communist Party of Australia, but she left the movement due to her growing conservative beliefs. Incidentally, as she aged, Emmeline found herself aligning with conservative values. By the late 1920s, Emmeline was invited to stand as a parliamentary candidate for the Conservative Party. She could not forge an alliance with the Liberals or Labour Party, due to their previous history of marginalising women’s issues, hence why she turned to the Conservatives.[10] So, the political views of both Adela and Emmeline changed during the interwar period, which also marked a shift in their relationship. This suggests that Emmeline’s final years no longer revolved heavily around activism. Moreover, the years of hunger strikes had left Emmeline with ill health, which could explain why she sought to make peace with her youngest daughter.

Christabel Pankhurst was also part of the reason why both the younger Pankhurst sisters had feuds with their mother. There may have been jealousy from Sylvia and Adela due to their mother’s special relationship with her eldest child. Almost certainly, Christabel was the clear favourite child of Emmeline’s. She was the chief strategist of the WSPU, and like her father, she earned a law degree. According to Professor June Purvis, Emmeline appears never to have disagreed with Christabel during the long suffrage struggle.[11] Rather, Christabel acted as Emmeline’s second-in-command; the two were unanimous in their political views. Thus, Sylvia and Adela may have felt slightly threatened, as Christabel was so highly regarded by Emmeline. Therefore, Emmeline’s special relationship with Christabel may have had an adverse effect on the younger sisters; but since Christabel worked more closely with Emmeline in their activism, it is unsurprising that their views were more aligned.

Emmeline faced pressures to conform to feminine ideals as a mother, whilst taking on a high-profile position as a controversial public activist. Her time spent campaigning for the enfranchisement of women caused personal divisions within her household. She had stringent expectations for her fellow WSPU activists, as Sylvia, Adela and Christabel knew all too well; but Emmeline perhaps held the highest expectations for her daughters, politically and morally. As the events of the early twentieth century unfolded, all of the Pankhurst women experienced shifts in their political views, which unfortunately resulted in Sylvia and Adela becoming estranged from the family. But it was Emmeline who endured several emotional traumas in her lifetime, all the while being a committed and charismatic leader who never gave up in the struggle for the women’s vote. As Sylvia described her mother’s legacy in The Manchester Guardian in 1930: “She remains to us as we knew her in the days of her greatness: the pioneer of new causes, the friend of the poor, the suffragette.”[12]

Sources:

[1] The Project Gutenberg EBook, EBook of My Own Story by Emmeline Pankhurst, (London: 1914), University of Toronto Libraries, <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34856/34856-h/34856-h.htm> [Accessed: 16 October 2020], p.1.

[2] June Purvis, ‘Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928), Suffragette Leader and Single Parent in Edwardian Britain’, Women’s History Review, 20:1, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09612025.2011.536389?needAccess=true> [Accessed: 6 August 2020], p.89.

[3] Katherine Connelly, Sylvia Pankhurst: Suffragette, Socialist and Scourge of Empire, (London: Pluto Press, 2013), p.31.

[4] Purvis, p.89.

[5] Ibid, p.92.

[6] Ibid, p. 101.

[7] “The Pankhursts: Politics, protest and passion”, The History Press, <https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/the-pankhursts-politics-protest-and-passion/> [Accessed: 12 August 2020].

[8] “Transcript: CRIM 1/139/2”, Emmeline Pankhurst, The Suffragettes: Deeds not Words, The National Archives, Learning Curve, pp.2-23, <https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/education/suffragettes.pdf pp.2-23> [Accessed: 09 September 2020], p.12.

[9] “Adela Pankhurst”, Working Class Movement Library, <https://www.wcml.org.uk/our-collections/activists/adela-pankhurst/> [Accessed: 26 August 2020].

[10] June Purvis, “Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biographical Interpretation”, Women’s History Review, 12:1, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09612020300200348> [Accessed: 02 October 2020], p. 94.

[11] Purvis, p.98.

[12] E. Sylvia Pankhurst, ‘Mrs Pankhurst: A Daughter’s Memories’, Manchester Guardian, 6 March 1930, ProQuest Historical Newspapers, p.9. <https://search.proquest.com/hnpguardianobserver/docview/478012627/pageviewPDF/F4E0BD7A2B76400EPQ/1?accountid=12253> [Accessed: 29 July 2020].

The Pankhurst Family and Politics: Part One

Written by Saima Akhtar (Twitter: @saimathewriter)

Supervised by Dr Charlotte Wildman (Twitter: @TheHistoryGirrl)

Our Twitter: @Ch_Domesticity

As part of our Challenging Domesticity in Britain, 1890-1990 research network, we are dedicating a blog post to the extraordinary suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst.

Read Part One of our blog post below:

Part One

Emmeline Pankhurst, neé Goulden (1858-1928). The Manchester-born leader of the suffragette movement was a wife, a mother, a businesswoman and activist. It was Emmeline’s relentless campaign for women’s suffrage which ultimately paved the way for the passing of The Representation of the People Act in 1918, an important pre-cursor in granting British women the parliamentary vote. But Emmeline’s activism became a source of anxiety and tension within her family. This article examines the ways in which the relationships between Emmeline and her daughters were characterised by political divisions and personal tensions.

Raised in an intellectual family who encouraged newspaper reading and political discussions, this prepared Emmeline well for a life centred on activism. The Gouldens were vocal about their political beliefs: Emmeline’s parents supported women’s voting rights and her grandfather had attended the Peterloo Massacre in 1819. Emmeline’s career began in London, where she advocated for women’s rights and allied herself with trade unions and socialists. After a brief hiatus from public activism, Emmeline returned to Manchester, where her passion for women’s rights was soon invigorated.

In 1903, Emmeline co-founded the female-only organisation, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in the parlour of her home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester. Women in Britain could not vote during this time, so Emmeline spearheaded the WSPU’s campaign for women’s suffrage. Firstly, Emmeline unsuccessfully canvassed for a Bill to be introduced in Parliament that would enfranchise married and unmarried women. [1] The Conservative government of 1885-1906 was divided on the issue of women’s suffrage. Some Conservative politicians understood that extending the vote to women could equate to more votes for their party. But many Members of Parliament did not support the idea of enfranchising women. Some found the idea of changing the status of women personally distasteful. Others ignored the women’s suffrage debate because they prioritised more pressing matters such as nationwide industrial unrest. So the WSPU campaign continued.

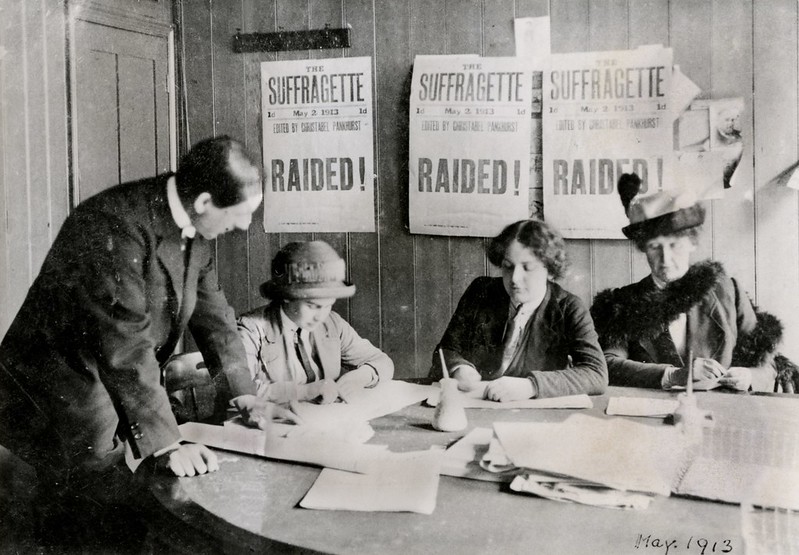

After her suffrage Bills faced rejection and after rejection in Parliament, Emmeline insisted that militancy would be the only way for the public to take notice of the struggle for women’s rights. The WSPU women began adopting militant tactics, including heckling politicians, chaining themselves to statues and railings, and smashing windows. These activities helped the WSPU garner plenty of press attention, because the women successfully turned their demonstrations into a public spectacle. The women knew that the sight of them protesting in dramatic ways would provoke shock, horror or even support from many readers, which helped them publicise their cause. Most newspaper reports criticised the WSPU’s militant action, especially when some of the women committed arson and bombed buildings. The Manchester Guardian took the most positive approach to covering suffragette campaigns.

At public meetings, Emmeline repeatedly questioned whether government leaders would grant women the vote, which often led to the WSPU women being violently removed from the room. Prepared to face jail sentences and endure hunger strikes for the cause, Emmeline also became subjected to force-feeding in prison.

Credit: LSE Women’s Library Collection

Outside of suffragism, Emmeline was involved in philanthropy. As a Poor Law Guardian, she arranged for food and provisions to help support the inmates of Manchester workhouses. She also served on the Manchester School Board, where she realised that female teachers were overworked, underpaid and less valued than male teachers were.[2] This inequality in education was another factor which motivated Emmeline to protect the interests of women.

When Emmeline lived in London, she owned and worked at a shop which sold fancy goods such as silk fabrics. Thus, Emmeline’s life was extremely busy and she faced a number of personal and professional challenges that affected the dynamic of her household.

Although Emmeline was in a happy marriage to her husband, the lawyer and socialist Dr Richard Pankhurst, who fully supported her endeavours, their family unit was marked by many personal tragedies. In 1898, Dr Pankhurst died suddenly, just months after the couple lost their infant son, Frank. This left Emmeline as a single mother to her three teenage daughters (Christabel, Sylvia and Adela) and her eight-year-old son, Harry. As a widow, Emmeline had debts to pay off, as well as the responsibility of financially supporting and educating her children. Tragically, Harry later passed away, at the age of twenty.

Following Dr Pankhurst’s death, Emmeline took on a paid job as Registrar of Births and Deaths in Manchester. Many poor women were relieved to come to a female Registrar to register the births of their illegitimate children, which Emmeline was deeply touched by. [3] These experiences further fuelled Emmeline to advocate on behalf of women’s rights.

Emmeline faced much emotional upheaval in her home life, which she was forced to process alongside her public work. So, how did Emmeline’s activism co-exist alongside the expectations placed on her as the mother of four children? In her 1914 book My Own Story, Emmeline recalls that she was, initially, “deeply immersed” in domesticity, but: “I was never so absorbed with home and children, however, that I lost interest in community affairs.”[4] Here, Emmeline may have felt pressured to focus on motherhood, particularly in light of the emphasis placed on maternalism in nineteenth-century constructions of femininity; but she deemed her activism too important to compromise on.

Emmeline’s public work created difficulties for her second daughter, Sylvia. A talented and trained artist, Sylvia was commissioned to create original works of art, including a series of paintings of working-class women in industrial communities. She also designed banners and posters for suffragette campaigns and served as the honorary secretary of the WSPU. In 1906, Emmeline wanted the position of secretary to be transferred from Sylvia to her eldest daughter Christabel, who was studying law at the University of Manchester. But Sylvia decided to rebel by handing in her resignation early. This was because Sylvia did not support Christabel as a political leader, on account of their differing opinions.

In fact, Sylvia was “not fully in accord with the spirit of (Christabel’s) policy”.[5] Sylvia was unwilling to work alongside Christabel due to their political differences. As a socialist, Sylvia was affiliated with the labour movement, so she was motivated to campaign alongside trade unions and fight for wider social change. In contrast, Emmeline and Christabel believed that the struggle for women’s rights should be the only goal for the WSPU.

Additionally, Sylvia suspected that Christabel, early on, shaped her “hope and policy on the speedy return of a Conservative government”, which turned out to be true.[6] So, politics affected the Pankhurst family dynamic, as Sylvia and Christabel clashed on issues relating to leadership, strategy and political ideology.

The year 1907 brought unrest within the WSPU, as Emmeline’s leadership faced inside threats. The ways that the Pankhurst women dominated the WSPU made some members, including organiser Teresa Billington-Greig, feel marginalised. So, Teresa intended to gain control as a delegate. This represented a challenge to Emmeline’s authority. So, Emmeline tore up the WSPU constitution, even though Sylvia, who wished to avoid this confrontation, wanted to keep it.[7] This highlights a difference between mother and daughter, as Emmeline acted tactically to curb this threat, even though Sylvia disapproved. Similarly, Sylvia refused to sign a new pledge which required WSPU members to promise not to support candidates of any political party until after women won the vote. [8] Christabel and Emmeline wished to engage with parties across the political spectrum because they wanted to appeal to women of all classes to support their cause.

However, this approach prompted Sylvia to break away from her mother and sister. Sylvia formed her own political faction, the East London Federation of the Suffragettes (ELFS). The ELFS did not attack the Labour Party, advocated mass protest and included men as members; these differences in policy caused Emmeline and Christabel to expel Sylvia and her group from the WSPU in early 1914.[8] These differences suggests political tensions aggravated relations between the Pankhurst women, as Sylvia’s independent path prompted her removal from Emmeline’s inner circle.

Watch out for Part Two of this blog post, coming soon!

Sources:

[1] The Project Gutenberg EBook of My Own Story by Emmeline Pankhurst, (London: 1914), University of Toronto Libraries, <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34856/34856-h/34856-h.htm> [Accessed 16 October 2020], pp.20-22.

[2] The Project Gutenberg EBook, pp.33-35.

[3] Ibid, pp.32-33.

[4] Ibid, pp. 12-13.

[5] Katherine Connelly, Sylvia Pankhurst: Suffragette, Socialist and Scourge of Empire, (London: Pluto Press, 2013), p.25.

[6] Connelly, p.27.

[7] Ibid, p.28.

[8] Ibid.

‘Activism & The Home’ Video Lecture 3: Thinking about Women, the Home, and ‘What Counts as Activism?’

As part of our AHRC funded project Challenging Domesticity in 1890-1990 project, we are hosting a series of video lectures from academics based on the theme ‘Activism and the Home’.

In this video, Lecture #3, Jessica White discusses the topic of women’s activism and mothers’ groups.

Jessica White is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Manchester. An historian of Modern Britain, Jessica’s research interests include gender, race, class and sexuality.

A transcription of Jessica’s video lecture can be accessed here:

You can find out more about Jessica’s work below:

Follow us on Twitter: @Ch_Domesticity

Email us: challengingdomesticity@outlook.com

‘Activism & The Home’ Video Lecture 2: Challenging the ‘Perfect Housewife’ Stereotype in Postwar Britain

As part of our AHRC funded project Challenging Domesticity in 1890-1990 project, we are hosting a series of video lectures from academics based on the theme ‘Activism and the Home’.

In this video, Lecture #2, Prof. Caitriona Beaumont gives a presentation on the topic: ”Who wants to be “Mrs 1963?”: How housewives’ associations challenged the stereotype of the perfect housewife in postwar Britain’.”

Prof Caitríona Beaumont is Professor of Social History in the Division of Social Sciences at London South Bank University. Caitríona works on the history of female activism, female networks and women’s movements in Ireland and Britain throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century.

You can find out more about Caitríona’s work below:

https://www.lsbu.ac.uk/about-us/people/people-finder/dr-caitriona-beaumont

Watch out for more Video Lectures from academics, posted here, every Friday!

Follow us on Twitter: @Ch_Domesticity

Email us: challengingdomesticity@outlook.com

‘Activism & The Home’ Lecture 1- Adult Education in Middlesbrough

Challenging Domesticity in Britain, 1890-1990 is an AHRC funded project hosted by the University of Manchester and The Pankhurst Centre, Manchester.

As part of our Challenging Domesticity project, we are hosting a series of video lectures from academics based on the theme ‘Activism and the Home’.

In this video, Lecture #1, Aleena Din discusses her research on British-Pakistani women in Middlesbrough.

Aleena is a DPhil Student at the University of Oxford. Her research topic is ‘Women in Britain’s Mirpuri-Pakistani Diaspora and their Relationship to Formal and Informal Labour, 1962-2002. ‘ You can find out more about Aleena’s work below:

https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/people/aleena-din

Watch out for more Video Lectures from academics, posted here, every Friday!

Follow us on Twitter: @Ch_Domesticity

Email us: challengingdomesticity@outlook.com

Challenging Domesticity: ‘Anne Lister and The Deviant Home’

As part of the AHRC-funded ‘Challenging Domesticity in Britain’ project, we were thrilled to welcome historian Dr Jill Liddington to the University of Manchester for a public lecture on ‘the first modern lesbian’, Anne Lister. Dr Liddington’s book Nature’s Domain (2003) inspired the hit BBC series Gentleman Jack, which examines Anne Lister’s life. Given that October 8 is International Lesbian Day, the lecture was a very exciting opportunity to delve deep into the story of an icon of British LGBTQ history.

Portrait of Anne Lister (Photo by West Yorkshire Archive Service)

Born in Halifax, West Yorkshire, in 1791, Anne Lister was a highly educated entrepreneur who travelled the world and owned shares in male-dominated industries such as mining. With her ‘masculine’ persona and refusal of heterosexual marriage, Lister was unconventional, particularly due to her romantic encounters with women. One female companion in particular- a less wealthy heiress named Ann Walker- moved in with Anne Lister at Shibden Hall, the Tudor-style property which ‘Gentleman Jack’ herself had inherited. Remarkably, the pair even took Holy Communion together on Easter Sunday in 1834, during a time when lesbian relationships were not visible in polite society.

Shibden Hall, West Yorkshire. (Photo by Calderdale Museums)

Whilst travelling in Georgia with Ann Walker in 1840, Lister died of a fever. She was buried in a church in her hometown. Shibden Hall was left to her lover, but sadly, Ann Walker was declared insane and later became confined to an asylum.

Anne Lister is survived by her diaries, where she detailed the chronicles of her love affairs. In fact, the four million words of her journals are written using an amalgamation of Greek letters, symbols and numbers. Though notoriously difficult to read, this code was eventually cracked by Anne Lister’s indirect descendant, John Lister, who was shocked by his discovery. So sensational are Lister’s passionate entries of female homosexuality, the first of its kind in historical record, that the works have been coined ‘the Dead Sea Scrolls of lesbian history’.

Everyone in the room enjoyed listening to Dr Jill Liddington’s presentation. Following the lecture, we were treated to a wine reception at The Pankhurst Centre. A fitting tribute to the English diarist who handled the finances, collected rent and oversaw all the business enterprises of her family estate- showing that ‘the home’ was much more than just a domestic refuge for nineteenth century women.

Follow us at @Ch_Domesticity on Twitter to keep up to date about our next events.

Written by Saima Akhtar, Network Coordinator for Challenging Domesticity in Britain, 1890-1990.